Gels are omnipresent in aquatic systems

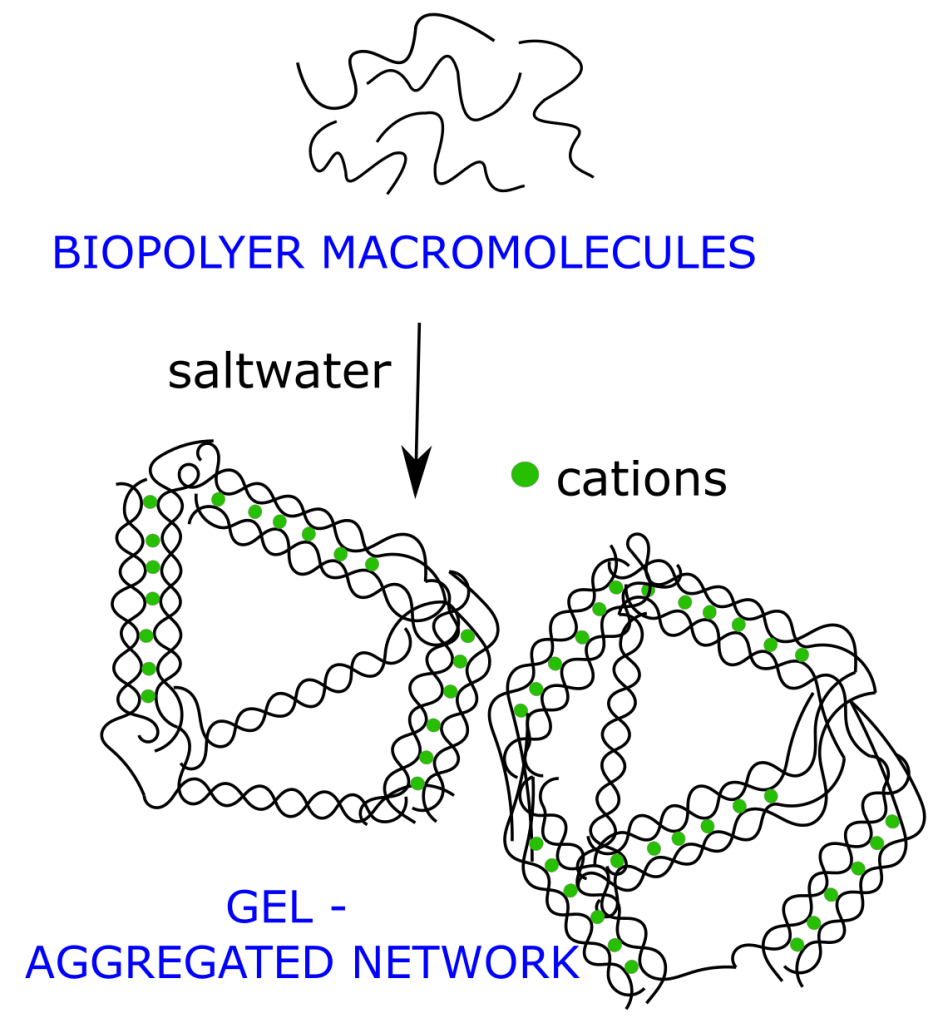

Gels are formed by biopolymers—such as polysaccharides and proteins—released by algae, bacteria, and other organisms into the surrounding water, where they are collectively termed exopolymers (EPS). These macromolecules create physical gels linked by weak bonds (electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonds) and occur across a wide range of sizes. Dissolved or colloidal EPS molecules can associate into micron-scale Transparent Exopolymer Particles, centimetre-scale marine (or lake, riverine) snow, and even larger macroaggregates. Their inherent stickiness promotes aggregation with other particles, facilitating the formation of mixed agglomerates containing algae, bacteria, mineral grains, and pollutants. Gels may appear as discrete, sparsely distributed particles in otherwise “clear” water, or they may occupy large volumes, transforming the environment into a mucus-rich medium, as often observed during intense algal blooms.

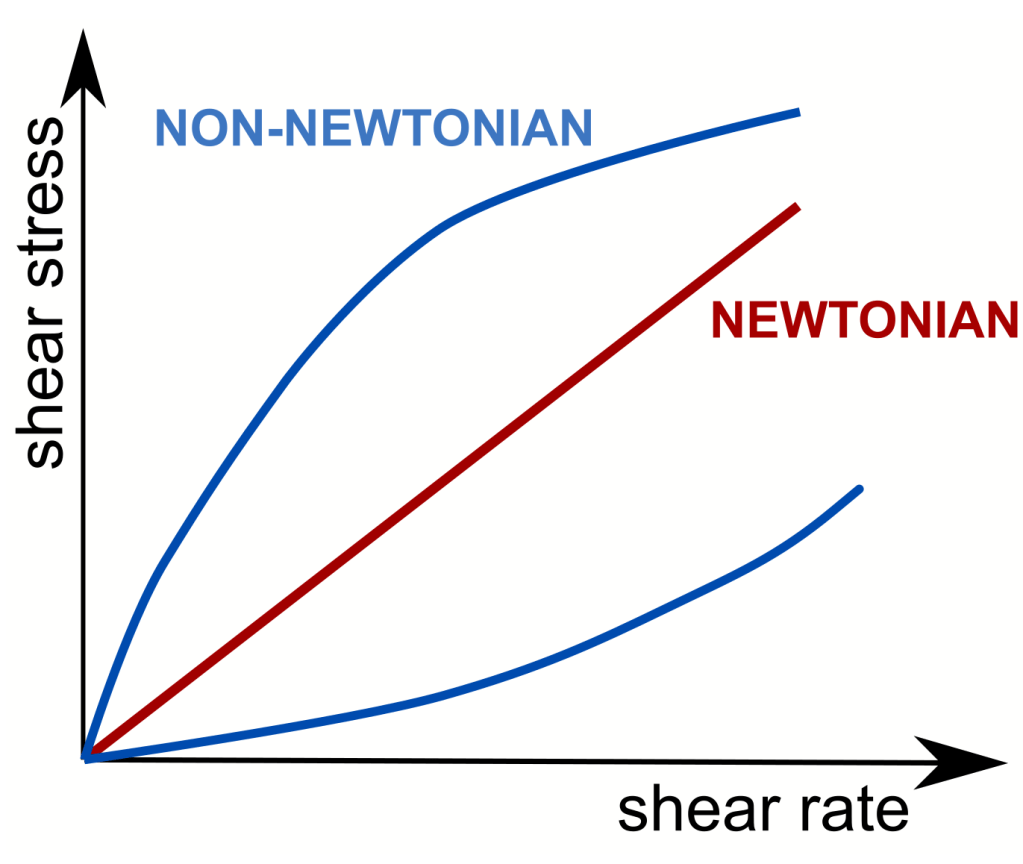

Algal bloom–afflicted water can transform into a non-Newtonian medium

When exopolymers accumulate in excess, natural water can shift from a Newtonian to a non-Newtonian medium. Rheology—the study of material deformation and flow—distinguishes these behaviours. In Newtonian viscous flow, shear stress (a force acting parallel to a surface) is proportional to shear rate (the rate of deformation) through a constant viscosity that reflects the fluid’s internal resistance. In EPS-rich, non-Newtonian water, this proportionality breaks down: viscosity changes with increasing shear because the exopolymer network undergoes structural rearrangements. In addition, mucus-rich water acquires solid-like properties expressed as elasticity; together, its liquid- and solid-like responses define its viscoelasticity. Through these mechanisms, microorganisms fundamentally alter the rheology of water, imparting non-Newtonian characteristics that significantly modify the microscale physics underlying environmental processes.